Blockchain technology has revolutionized decentralized systems by enabling secure, transparent, and immutable record-keeping without a central authority. At its core, consensus mechanisms ensure that distributed nodes agree on the state of the blockchain, making them a critical component of blockchain performance, security, and scalability. However, these mechanisms face significant challenges, including energy consumption, scalability, security vulnerabilities, centralization risks, and regulatory compliance. Below, we explore these challenges and review proposed solutions from recent research.

The most popular consensus mechanisms are known as the proof-of-work (PoW) and the proof-of-stake (PoS).

Beyond PoW and PoS, there have emerged dozens of different consensus mechanisms that represent novel or hybridized versions of the aforementioned mechanisms. Each attempt to solve the Byzantine Generals’ Problem in various ways. These include:

- Proof-of-Activity (PoA)

- Proof-of-History (PoH)

- Proof-of-Importance (PoI)

- Proof-of-Capacity (PoC)

- Proof-of-Burn (PoB)

- Proof-of-Authority (PoA)

- Delegated Proof-of-Stake (DPoS)

- Proof-of-Elapsed Time (PoET)

Challenges and Solutions

Challenge 1: Energy Consumption

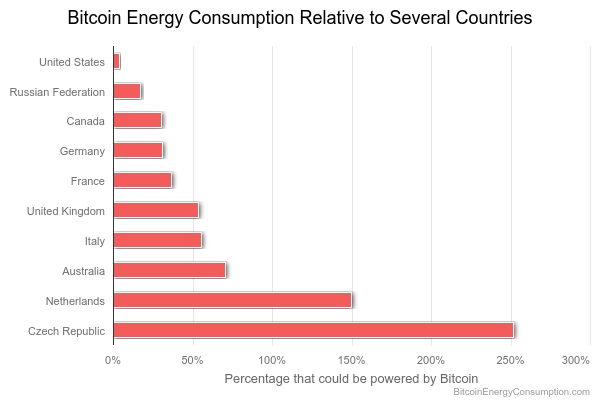

Proof-of-Work (PoW), the original consensus mechanism used by Bitcoin, is notoriously energy-intensive. Miners compete to solve complex mathematical puzzles, consuming significant computational power. Bitcoin’s energy usage rivals that of the Netherlands (150 TWh annually), raising environmental concerns and conflicting with global sustainability goals.

Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index:

This inefficiency limits PoW’s applicability in regulated financial services and broader adoption.

Solutions and Proposals:

- Proof-of-Stake (PoS): Reduces energy use by selecting validators based on staked assets. Ethereum’s 2022 PoS transition cut energy by over 99%. However, it risks centralization.

- Proof-of-Elapsed-Time (PoET): Assigns random wait times, minimizing energy. Studies suggest its viability for permissioned networks, though probabilistic settlement persists.

- Hybrid Mechanisms: Delayed Proof-of-Work (DPoW) leverages PoW security with reduced energy via secondary chains, balancing efficiency and robustness.

Challenge 2: Scalability

Handling a high volume of transactions per second (TPS) — remains a bottleneck. PoW, with Bitcoin’s 7 TPS, pales in comparison to traditional systems like Visa (1,700 TPS). Even PoS and DPoS, while faster, struggle with scalability in large networks due to communication overhead or validator bottlenecks. Public blockchains often sacrifice throughput for decentralization, exacerbating the “blockchain trilemma” (security, scalability, decentralization).

Solutions and Proposals:

- Sharding: Divides the blockchain into parallel shards. Ethereum 2.0’s sharding aims for higher TPS, though it increases complexity.

- Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs): IOTA’s Tangle processes transactions in parallel, enhancing scalability but compromising some security.

- Parallel Consensus: BBCA-Chain’s parallel BFT boosts throughput in permissioned settings, with potential for broader use pending testing.

- Layer 2 Solutions: The Lightning Network offloads transactions off-chain, improving scalability but reducing transparency.

Challenge 3: Security Vulnerabilities

Consensus mechanisms are vulnerable to attacks like 51% attacks (PoW/PoS), Sybil attacks (PoET), and Byzantine faults (BFT variants), PoS the “Nothing at Stake” problem, threatening network integrity.

Solutions and Proposals:

- Enhanced BFT Variants: Federated BFT (fBFT) uses quorum slices for fault tolerance, as in Ripple, though unknown nodes pose risks.

- Punitive Measures: Ethereum’s Casper slashes stakes of dishonest validators, deterring misbehavior.

- Machine Learning (ML) Integration: ML-enhanced consensus predicts attacks, improving security, though real-world scalability is untested.

- Quantum-Resistant Protocols: Emerging designs counter future quantum threats, still theoretical.

Challenge 4: Centralization Risks

Despite blockchain’s decentralized ethos, many mechanisms trend toward centralization. PoW favors large mining pools, PoS / DPoS benefits wealthier stakeholders, and private mechanisms like DiemBFT (with $10M entry barriers) concentrate power. Centralization undermines contestability and resilience, risking “too big to fail” scenarios.

Solutions and Proposals:

We are offering you check a few consensus mechanisms based on voting as explained by Dr. Leemon Baird to get a better insight into the matter:

- Reputation-Based Voting: Hybrid DPoS with reputation rewards decentralizes validator selection, needing robust metrics.

- Dynamic Validator Sets: EOS’s BFT-DPoS reduces cartels via dynamic delegation, though voter turnout remains low.

- Agent-Centric Models: Holochain eliminates global consensus, enhancing decentralization but limiting transactional use.

- AI-Driven Node Selection: AI-managed clusters distribute roles, countering centralization in IoT contexts.

Challenge 5: Regulatory and Settlement Finality Issues

Probabilistic settlement in PoW, PoS, DPoS, and PoET clash with financial regulations requiring immediate finality while private mechanisms like pBFT/iBFT offer finality but raise competition concerns due to closed networks. Regulatory oversight is further complicated by pseudonymous participants in public blockchains.

Solutions and Proposals:

- Immediate Finality Mechanisms: pBFT, iBFT, and DiemBFT offer instant settlement, aligning with regulations.

- Regulatory Sandboxes: Testbeds ensure compliance without stifling innovation.

- Identity Integration: Proof-of-Authority (PoA) uses known identities for oversight, sacrificing anonymity.

- Cross-Chain Interoperability: Standardized settlement across chains aids regulatory harmony, though technically immature.

Future Directions

- Hybridization: Combining PoW security with PoS efficiency addresses the trilemma.

- AI/ML and Quantum Advances: AI-enhanced and quantum-resistant protocols promise adaptability and future-proofing.

- Sustainability Focus: Greener mechanisms like Proof-of-History (PoH) and Proof-of-Stake-Velocity (PoSV) gain traction.

- Scalability Innovations: Sharding, DAGs, and parallel BFT drive high-throughput systems.

Conclusion

Consensus mechanisms evolve to balance security, scalability, and decentralization amid regulatory and environmental pressures. While PoW’s energy issues spur PoS and PoET, scalability solutions like sharding and DAGs advance throughput. Security, centralization, and settlement challenges inspire innovative hybrids and AI/ML integration. Continued research and real-world testing are crucial to refine these proposals, ensuring blockchain’s transformative potential.

“We believe that blockchain technology could be an important tool for protecting and preserving humanity and the rights of every human being, a means of communicating the truth, distributing prosperity, and—as the network rejects the fraudulent transactions—of rejecting those early cancerous cells from a society that can grow into the unthinkable.”

Don Tapscott, Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin and Other Cryptocurrencies is Changing the World

Definitions

- Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT): A set of technological solutions that enables a single, sequenced, standardized, and cryptographically secured record of activity to be safely distributed to, and acted upon by, a network of varied participants. This record can contain transactions, asset holdings, or identity data. Through nodes, DLT is used to maintain and share digital records instantaneously across a network of participants.

- Blockchain: DLT in its blockchain form was first used in Bitcoin to facilitate peer-to-peer payments without a central third party. Blockchain is a type of DLT that has a specific set of features, organizing its data in a chain of blocks. Each block contains data that are verified, validated, and then “chained” to the next block. Blockchain is a subset of DLT, and the Bitcoin Blockchain is a specific form of a blockchain.

- Consensus mechanisms: Consensus in distributed systems is ensuring that a state, value, or piece of information is correct and agreed on by most nodes. A consensus mechanism guarantees this effort is carried out fairly and independently of any interested party, or in the case of private permissioned networks, to achieve other objectives desired by the network (such as centralized control).

- 51 percent attack: An attack in which malicious actors gain control over 51 percent of nodes in a network

- Bali Fintech Agenda: A framework developed jointly with the World Bank to help authorities balance the benefits and risks of new technologies in financial services

- Hashrate: The speed of mining measured as the computational power per second used

- Mining pool: The pooling of resources by miners, who share their processing power over a network, to split the rewards

- Nodes: A DLT connection and communication point that can create, receive, send, and act on information

- On / Off-ramps: Usually, centralized points of a crypto-asset ecosystem that allow fiat currencies to be exchanged for crypto assets—for example, trading platforms

- P2P protocol: Determines inter-node communication, including how blocks and transactions are exchanged

- Permissioned / Closed networks: Networks in which only known actors with specific rights can validate existing records and add new ones

- Permissionless / Open networks: Networks in which anyone is allowed to validate existing records and add new ones

- Private networks: Networks in which visibility is restricted to a subset of users

- Public networks: Networks in which all users can see records being added or changed

- Quorum: The number of nodes required to reach agreement

- Regulatory Sandbox: A controlled environment overseen by a regulatory authority that allows firms to test their innovative propositions with real consumers

- Sharding: Sharding is a database partitioning technique used to enable scalability in blockchains. It also allows them to process more transactions per second. Sharding splits a blockchain network into smaller partitions, known as “shards.” Each shard is composed of its own data, making it distinctive and independent when compared to other shards. Sharding can help reduce the latency or slowness of a network since it splits a blockchain network into separate pieces. However, there are some security concerns surrounding sharding, which might allow for attacks on the network.

- Sybil attack: An attempt to control a distributed network by creating multiple fake identities

- TechSprint: A technology-focused design sprint that brings together diverse participants to collaborate intensively over a short period of time on a software project

Resources: